Learn more about Construction Administration Manager, Craig Campbell, in his Staff Spotlight, where he shares his interests and motivations.

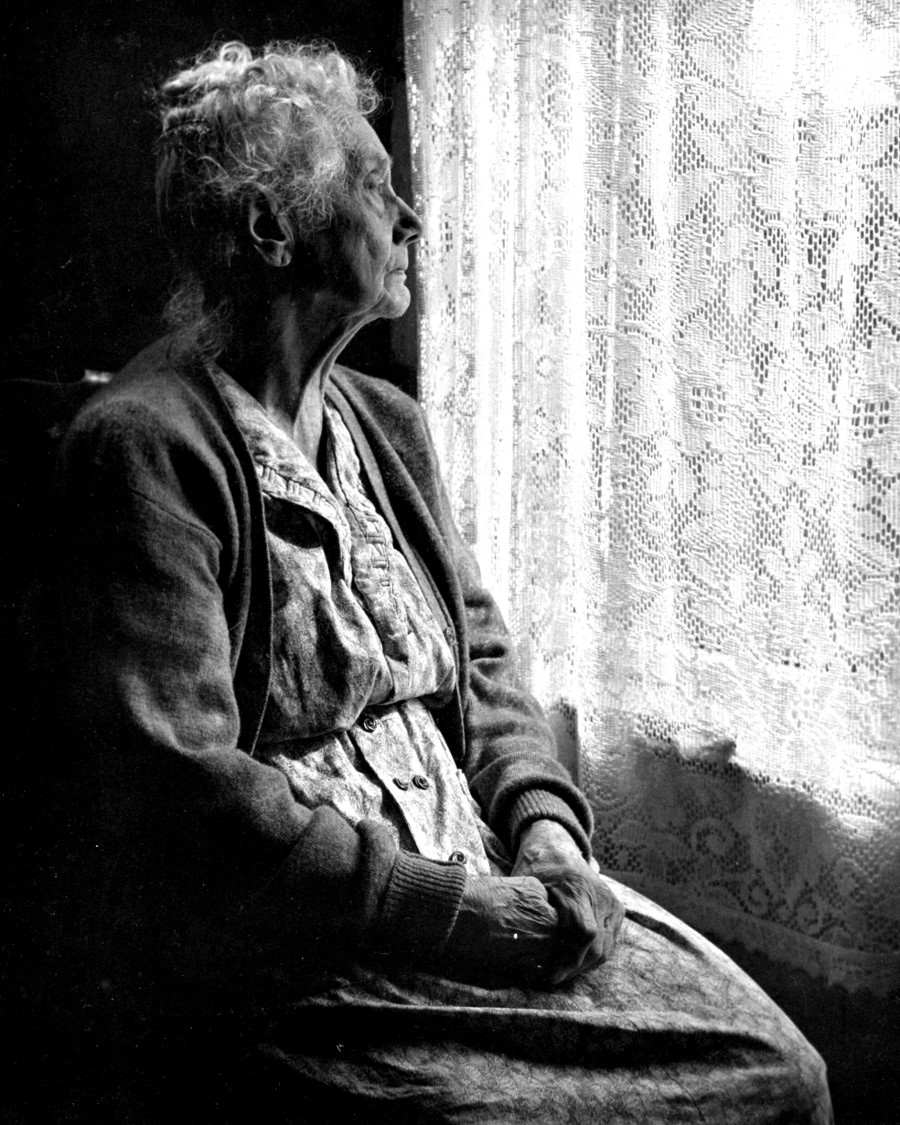

We are lonely as a culture. Some of us are lonelier than we care to admit. And we’re getting lonelier.

To many, it’s a confusing dilemma. How can the most connected society in human history be lonely? How can we feel isolated when almost every technological advancement in the last 60 years was conceived under the premise that it would increase connectivity? It appears that you don’t have to be alone to be lonely.

As the research surrounding loneliness continues to grow, so does the list of possible remedies. Studies clearly illustrate that the more technology we use, the lonelier we tend to feel. Nevertheless, emerging innovations like social robots – digital devices designed to provide companionship to isolated individuals in their homes – are rapidly growing. Ironically, it seems we are eager to look for answers by using the very methods that sparked the initial problem.

If we are serious about combating loneliness, we cannot afford to look towards artificial intelligence and technology for sustainable solutions. If this situation has taught us anything, it’s that there is no technology that can replace the intrinsic value of face-to-face communication. But how can we guarantee each other the meaningful personal connections we all so desperately need? What can we do to insulate people from the dangers of loneliness?

The answer might be simpler than we think. As Petula Clark sang in 1964: “When you’re alone, and life is making you lonely you can always go… downtown.”

We are social creatures that instinctively depend, both emotionally and biologically, on our role within a larger tribe. And no matter how much we persist; we can no longer afford to ignore millions of years of evolution. This is precisely why our downtowns matter. Their intrinsic true value isn’t reliant on an ability to attract emerging professionals or promote a budding microbrewery; it’s in their ability to exist as an effective platform for building social capital.

Since the earliest civilizations, each village, each downtown, existed to provide a predictable place to cultivate meaningful connections with other people. From bartering goods to sharing gossip, these areas served as a common ground for the development of interpersonal relationships. However, as the digital age ushered in a virtual economy that grew less reliant on a physical place for mutual transactions, many of us found ourselves distanced from the social activity once offered by the public realm.

As the number of people living in isolation continues to grow, we will be forced to reconsider the value of connectivity. More specifically, if we can’t learn to appreciate the urgency of this issue, we will soon be forced to confront the undeniable consequences that chronic loneliness will have on our communities – ramifications that will upend the economic well-being of many of our cities and towns.

The issue of connectivity is complicated by the competing interests of the global economy and the isolated individual. They both rely on efficient networks, but the latter requires physical connection to function properly. Unlike financial markets, people need a layered collection of casual acquaintances and close friends, connections they grow through frequent face-to-face communication.

The physical act of engaging with other people is the lifeline to our happiness and longevity. However, to sustain these connections requires a place in which we can maintain lasting relationships with the people we care about. To do this effectively, we need a reinvigorated public realm; one that understands its role as a shared platform for companionship.

Confronting Loneliness

The American Dream has, in part, always been infatuated with the value of privacy. The idea of the suburban home and the white picket fence was an aspiration for seclusion – qualifying success as the ability to isolate oneself from the larger community. It’s this mentality that inspired the home gym, home office, home school and home theater – amenities that were designed to remove ourselves from the public realm as validation of our success and independence.

This approach was an outgrowth of the original suburban condition. Dating back to the late 1800’s, the public realm was commonly seen as the source of our growing ailments, positioning our private homes as the places we went to escape and recuperate. It’s an outlook that no longer proves true. To the contrary, our modern obsession with privacy is precisely what’s damaging our health and, if we truly want to live healthier lives, we will need to retreat to the public realm in order to safeguard our well-being. But for many of us, that proves to be extremely difficult.

In the United States, more than 60 million people claim to be socially isolated and unhappy. More than half of them live alone, making it the highest proportion in America’s history. And while mere isolation doesn’t necessarily mean someone will become lonely, it does mean they have less physical interaction with other people with whom they care about and who care about them. And that alone can be deadly.

Emerging medical research shows a clear connection between loneliness and declining health, including increased risk of coronary heart disease, stroke, and dementia. It raises our cortisol and blood pressure levels and impacts our production of adrenaline, noradrenaline, and corticosteroids. Social connectivity, on the other hand, has the opposite influence. As Susan Pinker notes in her book, The Village Effect: How Face-to-Face Contact Can Make Us Healthier and Happier, “A rich social network of face-to-face relationships creates a biological force field against disease.”

This is becoming increasingly evident in cancer research. Socially isolated women are 66% more likely to die of breast cancer than women who have at least 10 friends they can count on. Pinker explained, “Those friends not only helped by providing information and concrete assistance, they also provided that neuroendocrine flush that comes with spending time with people you like and who care about you. And that means spending time with them, hearing the sounds of their voices and perhaps being touched. A hug, a squeeze, on the arm, or a pat on the back lowers one’s physiological stress responses, which in turn helps the body fight infection and inflammation. Being there is person is key.”

As we work to process this mounting data, we can’t help but project the impact this will soon have on our communities at-large. If we applied the consequences of chronic isolation proportionally across the millions of people reporting a deep sense of loneliness, the resulting figures would rival that of a national emergency. We need to do a better job framing the connection between loneliness and mortality if this issue has any hope of being given the attention it deserves.

When we look at the factors that can reduce our chances of dying, we immediately think of diet, exercise, and medicine – all of which can play a role in our longevity. But the research is clear. The most impactful strategies for increasing our expected lifespan is social integration (connections across a wide network) and strong relationships (close relationships that provide support). And while we can grow our social integration through a variety of ways, including digital networks, the critical development of strong relationships desperately relies on physical proximity.

Yet, if loneliness has such an undeniable impact on our health, and our strongest relationships tend to require a face-to-face interaction, what role does a community play in promoting or prohibiting social connectivity? It helps to define how we categorize these social connections in order to appreciate the role our civic spaces play in this equation.

First, there are bridging connections – the relationships that define the health of our social integration. These are weaker connections that define the larger network of people we know, but don’t necessarily have intimate relationships with. These are often most beneficial when we need something concrete – a house, a job, a new doctor – because they expose us to people and resources we couldn’t access otherwise. It’s here where social media, such as Facebook and LinkedIn, has provided substantive value.

They empower us to exponentially expand our bridged connections and expose us to a vast network of people and resources. The problem is, they seldom serve as a vehicle for developing more meaningful relationships, which is the primary indicator for loneliness.

The second group represents our bonding connections – the associations that define our strong relationships. These represent the people we are closest with, the ones that we rely on for support in our time of need. They are who we rely on if we need a ride to the airport; if we need to borrow money; or need a shoulder to cry on. They are the ones we share our most intimate information with and the ones that we would help at a moment’s notice.

These two interconnected networks are the basis from which we define our sense of community and our role within it. Emotions like happiness, contentment, success, and belonging are a direct result of how well we can balance these two types pf relationships.

However, once an imbalance occurs, the sense of isolation is inevitable. And for many of us, that is a fragile balance.

For bridged connections, our networks can be devastated by a sudden lack of internet access or by losing the ability to drive a car. Occurrences like these are often the primary hurdle for people trying to escape the challenges of poverty – populations that traditionally have smaller bridged networks. Bonded connections are even more delicate. Neglecting to keep in contact with people who are important to us is as dangerous to our health as a pack-per-day cigarette habitat, hypertension, or obesity.

Commonly, our bonded relationships consist of only one or two people (usually a spouse), leaving many of us dangerously close to feelingly entirely alone. No matter the health of our social networks, whether it be bridged or bonded, many of us are one catastrophe away from complete isolation – and that number is growing.

The sense of loneliness these experiences provide, that unmistakable feeling of despair and anxiety, is a natural response to isolation. The emotions we feel are a neurological response to being isolated; like hunger or pain, it’s a biological signal that alarms us that we have been separated from the group and are potentially in grave danger.

It’s an instinct that is heightened when we are at our most vulnerable, incentivizing us to reconnect with our tribe in hopes, as Petula Clark postulated, “You may find somebody kind to help and understand you, someone who is just like you and needs a gentle hand to guide them along.”

We rely on this connection and depend on places that protect our relationships with our bonded group. The problem is, for many of us, these places simply don’t exist.

Prescribing Villages

The fundamental role of our downtowns, or for any shared commons for that matter, is to provide an inclusive place to foster camaraderie – one that dedicates itself to incentivizing civic participation and social interaction. In order to combat the looming crisis of chronic loneliness, and the realities it imposes on those effected, communities will need to leverage social cohesion as the ultimate anecdote.

This isn’t a new idea. In fact, prioritizing the shared commons as a way to encourage communal attachment and connectivity is a hallmark of almost all great civilizations.

As Ray Oldenburg outlined in his influential book, The Great Good Place, “In both Greek and Roman society, prevailing values dictated that the agora and the forum should be great, central institutions; that homes should be simple and unpretentious; that the architecture of cities should assert the worth of the public and civic individual over the private and domestic one. Few means to lure and invite citizens into public gatherings were overlooked. The forums, colosseums, theaters, and amphitheaters were grand structures, and admission to them was free.”

However, this is not how most modern communities have approached the development of civic space over the past 50 years. While some have neglected their downtowns, many more have completely abandoned them all together.

But with the growing interest in downtown redevelopment, and a renewed desire for a vibrant public realm, many communities are exploring how to retrofit these priorities onto existing neighborhoods.

Ultimately, the challenge will be in exploring how best to neutralize the placelessness imposed by suburban sprawl and reintroduce a shared sense of attachment within our communities. To do this well will require a better understanding of how the places we provide can shape the human experience.

“The examples set by societies that have solved the problem of place and those set by the small towns and vital neighborhoods of our past suggest that daily life, in order to be relaxed and fulfilling, must find its balance in three realms of experience,” said Oldenburg. “One is domestic, a second is gainful or productive, and the third is inclusively sociable, offering the basis of community and the celebration of it. Each of these realms of human experience is built on associations and relationships appropriate to it; each its own physically separate and distinct places; each must have its measure of autonomy from others.”

There is a growing interest in adopting a methodology for community development that values a common set of interests – efforts that look to attract like-minded people that share a mutual set of values such as politics, religion, or industrial specialization; but, this can often result in homogenous pockets of inactivity.

Our communities don’t benefit from a collection of people dedicated to a specific ideology. We benefit from a collection of people dedicated to a specific place – a place that depends on cooperation and compassion to thrive.

The development of effective social cohesion is formed by the triangulation of these three fundamental places: home, work, and the shared commons. First, the home provides our primary dwelling as a realm of privacy, framing our sense of control and memory within our neighborhoods.

Secondly, the workplace provides a realm of purpose, whether it be paid occupation or volunteerism, where we can project our value onto the larger community.

Lastly, the third place is defined as the shared commons – a dynamic mechanism that provides a realm of fellowship.

These shared commons can exist in a multitude of forms – from public libraries to downtowns – but their purpose is universal. They are intended to provide a predictable platform for the development of meaningful relationships across a diverse collection of people. They exist as an oasis of sociability, available to anyone who needs to contest with the demons of loneliness.

The value of these shared commons is most easily seen in the role they play in supporting centenarians (people over the age of 100) throughout the world – communities commonly referred to as “Blue Zones.”

While scattered across the planet in remote and seemingly unconnected corners of the world, these places all shared consistent traits such as the diet and physical activity among older adults.

However, what is more noticeable is how socially engaged people are throughout the course of their lifetime. The vast majority of the centurions studied are traditionally involved in faith-based communities; benefit from immediate family living close by; and are active members in a tribe of friends that share healthy habits.

What these places teach us is that our involvement in a social network of people who regularly interact with one another is not only critical to how we measure our individual happiness, but it’s the determining factor in predicting our longevity.

The challenge is in ensuring people have the opportunity to inhabit places that allow them this regular interaction; too often, the environments in which we live are the sole reason we are unable to have meaningful relationships with the people we care about.

We understand the side effects of loneliness. We also understand what’s needed to alleviate the problem. This epidemic will not be remedied by prescribing new medicines. It will only be solved by prescribing a new village – a public realm that each of us can rely on for support.

The discussion of loneliness is largely one of civic duty. If we, as a culture, are sincerely interested in protecting the life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness for those living in our communities, we need to reconcile the role placemaking has in the health and well-being of our citizenry.

We need to remind ourselves that the responsibility of neighborhood development is in the opportunities they can consistently provide people of all ages, abilities, ethnicities, and orientations. It’s a strategy that acknowledges that justice is nothing more than love manifesting itself within the public realm. And it’s a discussion that reminds us that we can do better than this.

The places where we come together as a community aren’t simply locations for shared experiences. They serve as a common ground where we can grow together, providing us a platform to build stronger relationships and remind each other that we are on this journey together.

It’s like Petula Clark said: “So maybe I’ll see you there. We can forget all our troubles, forget all our cares. Things will be great when your… downtown.”

By Zachary R. Benedict, Principal

Note: This article was originally written for Fort Wayne Magazine.