MKM was named one of the Top Healthcare Architectural Firms in the U.S. by Modern Healthcare magazine for the 11th consecutive year.

Cooperation is a basic instinct. We find it prevalent all through nature, from large whales to ant colonies. Evolutionary biologists refer to it as “reciprocal altruism” – the desire to try and anticipate what others need and want. Humans are no different. Not only do we want to help others, we often want others to also be empathetic to our needs. This shared instinct inspires a relationship that relies on trust and rewards cooperation.

In 1979 a tournament was created by a young political scientist to explore the logic of cooperation. He asked people to submit a computer program to play the “Prisoner’s Dilemma” game 200 times against all other programs submitted. To their astonishment, the nicest and simplest program won. The winning entry, designed by the Canadian scientist Anatol Rapoport, was named “Tit-for-Tat” and simply began by cooperating and then mimicking the behavior of its opponent from the previous game. To everyone’s surprise, even the simplest computer understood the benefits of cooperation.

However, our ability to cooperate with others is often reduced by the environments in which we live. The design of our homes, workplaces, and neighborhoods play a significant role in how we perceive our sense of independence, meaning, dignity, and self-worth. In order for communities to engage people of all ages and abilities in a culture of health, we will likely need to better understand how to prioritize “reciprocity” over “authority.” To do that we will need to trust one another.

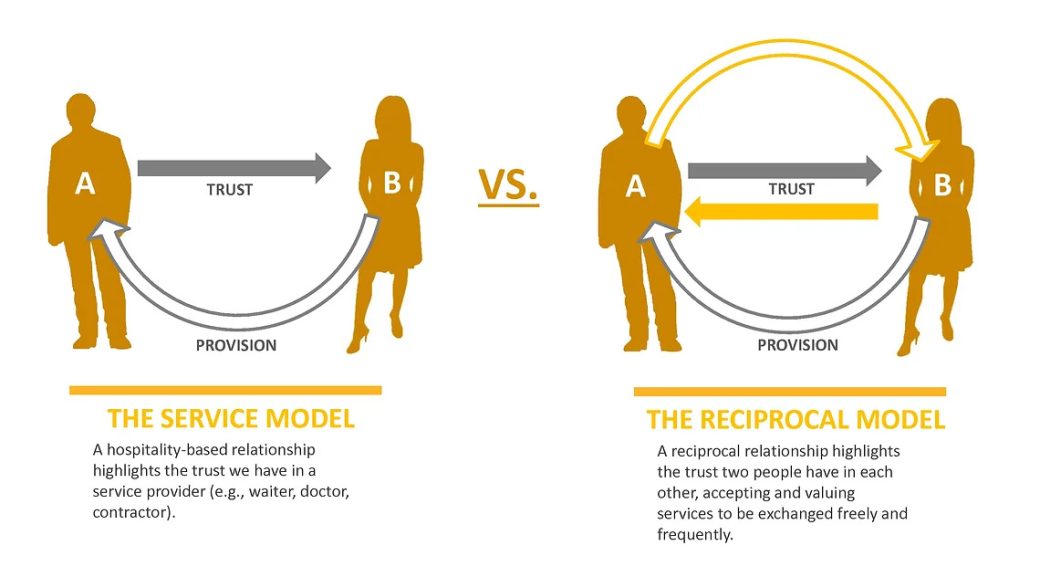

There are two basic types of relationships that describe this concept. First is the conventional “hospitality model,” a consumer-based service model highlighting the trust we have in a specific provider (e.g., doctor, dentist, plumber). In this model we trust someone to provide us with a service. The second model is a “cooperative model,” a reciprocal model highlighting the trust two individuals have in each other, each playing meaningful roles in achieving a common goal (e.g., borrowing a cup of sugar from a neighbor). While certain services can be effectively provided with a hospitality model, many would benefit greatly from a more cooperative model – one that both participants play a meaningful role. This is often a common dilemma in healthcare.

When it comes to the determinates of health, it’s hard to ignore the authority a seasoned physician possesses. Yet, in so many cases, quality care can only be provided through a cooperative approach, one that includes the patient in the identification of symptoms and the development of the diagnosis. Not only does the patient need to trust that the physician will provide excellent care, the physician needs to trust that the patient is providing accurate and reliable information regarding their condition. If this sense of trust fades in either party, the willingness to reciprocate dwindles. This is the balance between “authority” and “reciprocity.”

In order for there to be a more sustainable approach to population health management, this cooperative model needs to be considered at various scales. From the planning of communities to the design of exam rooms, there needs to be a consistent dedication to reciprocal relationships. Cooperation is a basic instinct, one that relies on well-designed places to thrive.