Placemaking for proximal health - prioritizing primary care

Note: In Placemaking for Proximal Health Part I, we focused on principles of primary care. Part II focused on prioritizing primary care.

It is often stated, you are who you surround yourself with.

More than likely, this isn’t the first time you’ve come across that sentiment. There’s truth behind it. The people we live alongside have a significant influence on us—for the better and for the worse.

Though the reciprocity concealed within this idea is frequently overlooked, many acknowledge its basic principle and take it to heart. We are dependent on and accountable to each other’s well-being more than we often are aware of or care to admit.

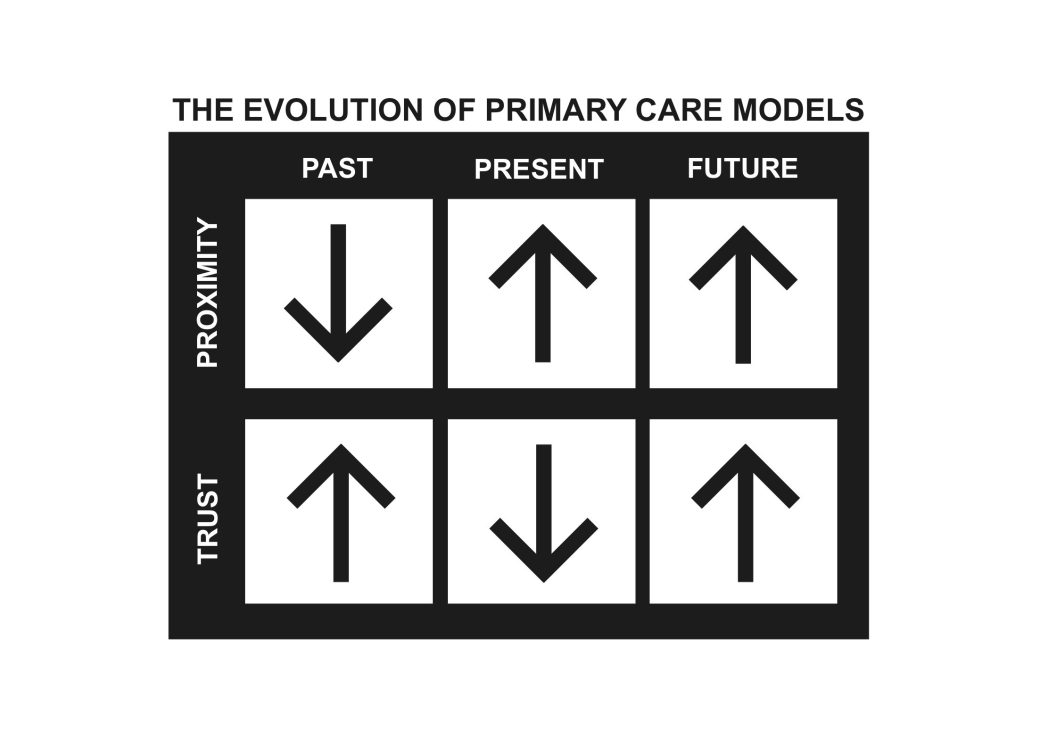

Each new year uncovers a myriad of threats to our well-being that influence our approach to healthcare and community development. Despite much progress, disparities across neighborhoods and places point to the ongoing challenges facing many communities throughout the Midwest. While not all health risks are controllable, the shape and functionality of our communities offer a unique way to manage these risks. Proximally locating primary care through social infrastructure has the potential to increase trust in primary care providers.

BORROWING SOCIAL INFRASTRUCTURE

Placemaking for Proximal Health is an approach which leverages social infrastructure as a platform for communities to naturally build relationships with their primary care providers. Supplying rural and urban communities designated facilities to freely interact with primary care providers can weaken geographic barriers that currently deter people from participating in many preventative health measures. Over time, the development of social infrastructure dedicated to providing primary care services can bolster collaborative care—a cooperative relationship between patients and their care team.

Research continually shows the importance of relationships to safeguard our health. A community that promotes well-being recognizes that people are its greatest asset, urging a devotion to care for and connect its members. Access to primary care should be a fundamental prerogative of belonging to a community. By properly positioning primary care as a community space, people are empowered with opportunities to maximize preventative health measures and connect with each other.

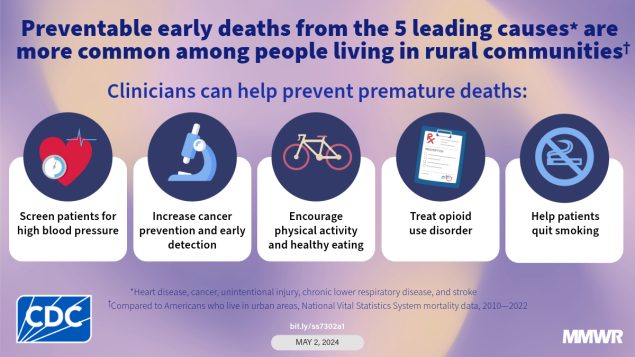

PRIMARY CARE IS PREVENTATIVE CARE.

When combating the leading causes of death in the United States, the guidance provided by primary care physicians is overwhelmingly important. According to the CDC, “the five leading causes of preventable premature deaths analyzed across all counties include: heart disease, stroke, cancer, unintentional injury and lower respiratory disease (CLRD)” (Garcia, et al., 2024). When routinely connected with their patients, clinicians can encourage and provide preventive care to alleviate these health burdens. The CDC notes several ways that clinicians can help prevent premature deaths including blood pressure and cancer screenings, encouragement of physical activity and healthy eating, treatments for opioid use disorder, and aiding patients to quit smoking.

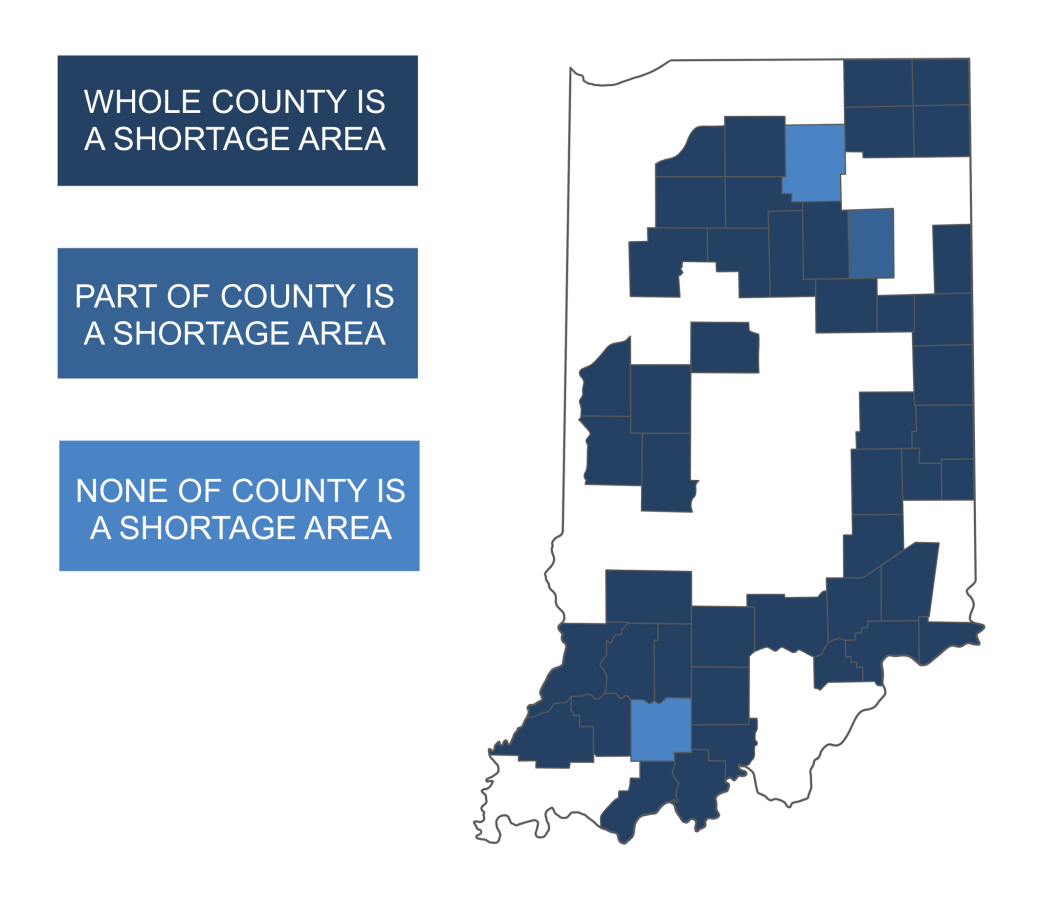

Rural communities in particular face higher health risks and poorer outcomes in preventable premature deaths when compared to more urban areas. Partly a result of geographic health inequities, many communities lack primary care services that support preventative health measures. In the U.S., 1,963 counties are classified as a ‘whole county HPSAs’ (Healthcare Provider Shortage Area). Of these 1,963 counties, 71.4% are nonmetropolitan counties. This corroborates the importance of positioning primary care providers within proximity to rural communities (NLM, 2022, Figure 20).

While it is clear that many rural populations suffer as HPSAs, “most people who live in areas designated as primary care HPSAs live in metropolitan counties because those counties are more densely populated (NLM, 2022, Figure 20). Understanding what distinguishes the geographic barriers of rural communities from more urban areas is important to properly positing primary care services in proximity to people. To connect people with their primary care providers, placemaking for proximal health right-sizes to specific community needs. As a result, efforts to reduce disparities between rural and urban areas should result in a decrease in preventable premature deaths for all populations.

Health Professional Shortage Areas: Primary Care, Indiana Nonmetropolitan

An Approach

The health of our communities depends on the relationships people can maintain with each another. For primary care professionals to build trust with their patients, they must be readily available to them. Placemaking for proximal health thoughtfully positions primary care providers within their service area to increase the likelihood that patients cross paths with their providers.

An article from KU Medical Center describes the benefits for both patients and healthcare providers in adopting proximal health concepts:

“It turns out that the same conditions that keep people healthy and thriving in ordinary life are exactly the same conditions that allow health care teams to achieve exceptional care outcomes. The list is short but powerful – being safe physically; feeling safe psychologically; knowing that you belong and are valued; feeling seen, felt, heard and appreciated for who you are and what you do; and being able to contribute in ways that make a difference. These fundamental human experiences relate directly to health and healing. Proximal health asks us to consider an idea that culture itself – the environments that surround us, thoughtfully structured and carefully nurtured – can be among our most important and effective instruments of care” – Dr. Uhlig (Geiszler-Jones, 2021).

In the same way that the people who surround you influence your well-being, so does the community that surrounds you. Almost ubiquitous forms of anchor institutions such as public parks, libraries, and schools, are presumed necessities that safeguard community well-being. The book, Palaces for The People, reminds us that, “In all neighborhoods, commercial establishments are important parts of social infrastructure. As Jane Jacobs and Ray Oldenburg famously argued, grocery stores, diners, cafes, bookstores, and barbershops draw people out of their homes and into the streets and sidewalks, where they create cultural vitality and contribute to the passive surveillance of shared public space.”

Placemaking for proximal health reasons that primary care facilities should also be included as a standard form of this social infrastructure. These places play a vital part in building relationships between community members—connections that help us build trust in places and services we depend on.

Chances are that the person who cuts your hair lives relatively close to you. Same for the mechanic who rotates your tires and the barista who you trust to craft a perfect latte each morning. Communities and healthcare systems should desire that people can depend on primary care services just as easily. Changes as radical and complicated as this, however, require gradual shifts over time and are sustained by a principal motive. Placemaking for proximal health understands that primary care falls short without the principal motive of trust—stressing the importance of sustained patient provider relationships.

When considerately integrated, our proximity to primary care through social infrastructure can increase our opportunity to become familiar with the professionals who protect our well-being, undoubtedly improving preventive health outcomes.

A Reminder

Oftentimes, our “do it yourself” world causes us to forget that we depend on the help of others every day. We learn to think that asking for help means we are weak or incapable. This innocent pride coaxes us into believing we are doing others a favor by figuring it out on our own. As selfless as it sounds, many of us spend our lives searching for ways to help others while simultaneously prohibiting others from helping us.

History is full of testimonies that show communities and people are strongest when they are willing to depend on each other. Reformation of our communal and individual well-being is no different. If our primary care physicians are going to support us, we must let them—by depending on them. Proximity to our primary care providers through social infrastructure can bolster trusted relationships and the health of our communities.