Placemaking for proximal health - prioritizing primary care

Once rooted in strong community ties, primary care established itself as the cornerstone of healthcare. Primary care is a collective term within healthcare that covers a range of services designed to promote community and individual health. Today, this field includes professions such as Public Health, Community Medicine, General Practitioners, Family Physicians, Preventative Medicine, Social Medicine, and many others (Turaman, 2024). Together, these fields have evolved into a complex web of health services, sharing the same goal to maintain and promote the health and well-being of our communities.

Placemaking for Proximal Health, the development of social infrastructure that supports primary care services, directly influences the effectiveness of preventive care in rural communities. Proximity to primary care through social infrastructure can increase trust in primary care services, improving the physical and social boundaries of our primary care providers.

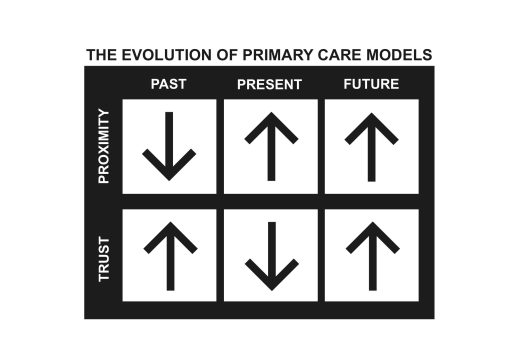

Access to quality healthcare is a key social determinant of health, charging placemaking for proximal health as a critical factor in improving community well-being. Though individual and community health is a multi-faceted issue, a historical perspective of healthcare services sheds light on the evolution of how proximity to primary care services and providers impacts the quality of care we receive. This evolution has challenged the core aspects of trusted physician relationships, presenting a substantial responsibility to prioritize the presence of primary care spaces within our communities.

Looking back

In the early 20th century, many rural towns relied on one or two resident physicians to provide all the healthcare needs within the community. Health information was limited and not widely available, meaning that primary care doctors took on a generalist role and were responsible for treating health concerns for all ages and abilities. General practitioners provided a wide array of care from managing routine illnesses to performing various surgeries. The unique expertise and services they provided usually meant that physicians were highly valued and respected community members.

Before the rise of specialization in healthcare, general practitioners were known to spend their time making house calls to meet patients in their homes. While many practitioners operated from a clinic, they often served simply as a place to store medical equipment and files. This indicates that a large portion of healthcare was provided through home visitation by the physician. The dedication and promise of general practitioners to provide care meant traveling long distances, whether on foot, by horse and buggy, or by car. Although many doctors saw their responsibility to protect the health of their community as a privilege, this mode of providing care was undoubtedly a strenuous lifestyle for practitioners.

Since formal health centers were not common in rural areas and doctors regularly traveled throughout their service area, they could offer care with an understanding of their patients’ family history, home life, social circumstances, and other environmental factors that may influence their health. Routine and familiar presence of practitioners allowed them to build strong relationships with their patients and proficiently address health concerns. Furthermore, especially in rural communities, general practitioners understood “that there was much more to assuring the health and wellbeing of their community than purely the provision of medical care within the walls of the exam room” (Miller xv). Primary care providers were known to be dependable neighbors who actively worked to protect the health and safety of the members of their community. In many ways, this past model of care echoes the expectations of healthcare today and prospers on the cooperation of community and individual health.

Proximity & Trust

While primary care today is largely dissimilar to what it once was, communities still depend on primary care physicians to support their health and well-being. By examining communities’ proximity to healthcare in the past, we can understand how placemaking for proximal health can contribute to more trusted primary care services.

As previously mentioned, it was typical for one or two general practitioners to provide care for a whole community. Though this would not be realistic for most communities today, there is still much to be learned from its success and limitations. Under this model of healthcare, general practitioners were known to be dependable because they consistently served one area. Over time, this almost guaranteed that patients knew their physicians, and physicians knew their patients on a more personal level. Repeated interactions with each other fostered long-standing relationships and cultivated trust that enhanced the quality of care.

Although general practitioners typically didn’t live within direct proximity to their rural community patients, their willingness to travel and meet patients in their home made the care they provided easily available to a wide audience. Since patients and physicians often had built sustained relationships over a period of time, doctors were trusted and able to treat conditions from a more holistic perspective considering the lifestyle and environmental factors influencing a person’s health.

A memoir from a 20th-century physician in Indiana describes the benefit of strong relationships in receiving care like this:

“There’s less anxiety when your mechanic knows your car’s history; less worry when your barber already knows how you want your hair cut; little or no stress when you trust your insurance agent to give you the best deal. In general, it’s more relaxing to live in a place where you feel connected to the people you see and do business with. And, as more and more research is revealing, less stress means better health” (Miller 69).

It’s easy to imagine how our experience of healthcare might improve if we knew that our doctor really knew us. Not only did the familiarity of a doctor enhance the quality of care, but the familiarity of the place also made receiving care less intimidating. The mere-exposure effect, explains why people are more comfortable with, and less afraid of, things that they are already familiar with. Although, the finite amount of healthcare facilities and vehicles in the early 20th century was likely the main reason that care was often provided in the home, the mere-exposure effect would suggest that because patients were served in a familiar environment, the provision of care was likely more comfortable than that which we receive in our healthcare facilities today. Learning from our past, we know that primary care providers which are familiar to us will increase our trust in the healthcare we receive.

Our built environment can improve both the physical and social dimensions of primary care by making services familiar through trusted social infrastructure. Effective placemaking for proximal health provides communities with a trusted space to easily access and experience the support of our primary care providers.

The transformative impact of placemaking for proximal health hinges on our proximity to social infrastructure that supports a relationship of trust with our primary care providers.

- Primary care that is readily available, because practitioners operate as a community resource.

- Care providers who are trusted because they know their patients through sustained relationships.

- Whole-person health is addressed by a comprehensive understanding of health-determining factors.

Moving forward, placemaking for proximal health can provide communities with access to a dependable and familiar environment in which to receive primary care services. Primary care should be available through community-based social infrastructure so that people can openly receive care and build relationships that promote their individual and community well-being.

A Starting Point

Of course, numerous factors other than our proximity to primary care social infrastructure affect the healthcare system at large. Breakthroughs in medicine and technology, population growth, and cultural shifts have entirely altered the way we navigate all kinds of community resources.

Naively, we’ve expanded and improved the capabilities of technology and medicine at the expense of quality human connections. All communities and individuals need primary care providers to protect their health and navigate their access to the larger health system. This demands that communities strategically orient our primary care services to make receiving preventative care more accessible. We need our primary care providers to be available, and that depends on us building communities that prioritize the relationships they foster with providers.

As a whole, we need to remind ourselves to take care of each other if we are going to capitalize on the incredible knowledge and medical innovations available to us today. The truth is, we feel our healthiest and find healing when we know we belong and that there are people who will be there for us when we need them most. And that reality can only be complimented, not replaced, by our next best multivitamin or version of telehealth.

It’s far from an overnight fix, but returning to our instincts, we can begin to cultivate communities where primary care is an integral part of social infrastructure and people shamelessly depend on each other for healing. This is the fundamental equation of placemaking for proximal health.