Congratulations to MKM architecture + design's Megan Crites for being nominated for the prestigious ATHENA Award!

Historically, hospitals were considered necessary institutions within a community, places reserved for those in need of care. However, today’s healthcare facilities are much more civic in their design and use – playing a meaningful role in the vibrancy and health of the communities they serve.

In a recent article for Medical Construction & Design, Edmund Einy notes that “As a result of this phenomenon, healthcare buildings are replacing city halls and shopping centers, becoming some of the most civic buildings and environments created and built today. Why? Because a healthcare facility may be one of the rare remaining buildings a person will physically need to visit during his or her lifetime, either for themselves or a loved one.” But it’s more than this.

As healthcare facilities continue to become more recognizable icons in their community (especially in rural settings), specific attention needs to be given to the civic qualities they provide. This not only provides an opportunity to redefine the “brand” of the facility but can also help demystify the reputation conventional healthcare facilities often have.

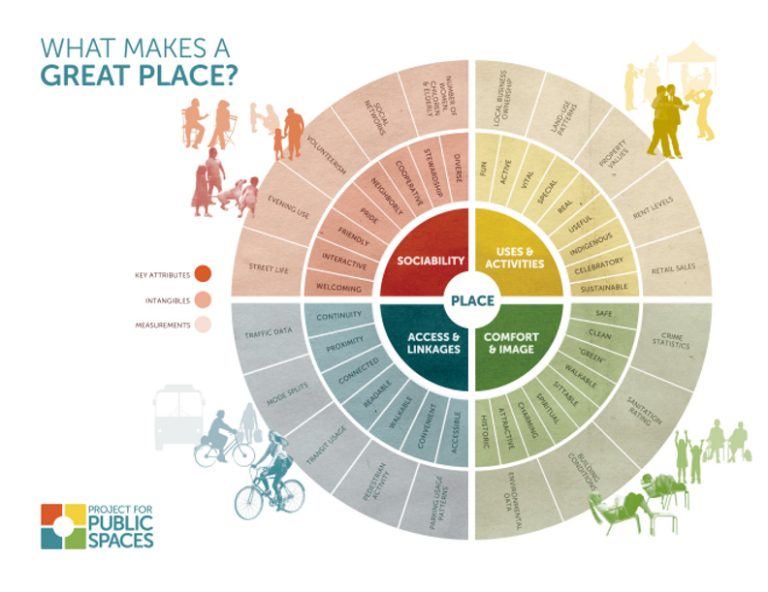

Civic icons are measured by their ability to provide engaging places for people to enjoy and this placemaking mentality is critical for healthcare facilities that are attempting to embrace a civic role. But how do we gage what makes a good civic space? Project for Public Spaces, an organization that has studied placemaking in over 3,000 communities worldwide, promotes that all successful places possess four key qualities:

- They are accessible. Their access and linkages are inviting to people of all ages and abilities.

- They are active. They provide things to do (and people to watch) throughout the day.

- They are comfortable. Their first impression promotes a clean, safe, and engaging place to visit.

- They are sociable. They encourage people to talk, allowing people to meet with friends and strangers alike.

As simple as these criteria may appear, each category brings with it considerations that, if done correctly, should reflect the nuances of each unique community. For example, what is “comfortable” for one group, might not be seen as “comfortable” for another. With that, the design of civic places must not only offer each of these elements in some way, but also provide a nimble design for them to evolve over time.

The difficulty of placemaking on healthcare campuses is found in the motivation of its occupants. The reason civic spaces are so vibrant and active is because the people using the space are there for a variety of different reasons. Some are there to people watch. Others are passing through while on an afternoon jog. Some are there to meet a friend for lunch. However, often times, healthcare facilities are primarily full of patients, patients’ guests, and staff solely focused on a preplanned care appointment or procedure. But how can this change?

As these facilities continue to evolve into primary civic spaces for the communities they serve, there will be a growing need to provide spaces and functions that attract people that have no direct care needs – individuals simply there to enjoy the campus as a civic space. As these placemaking strategies foster such experiences, the identity of the facility will change – shifting away from an intimidating care institution and move towards an approachable community center designed to foster socialization and promote well-being.